Where to Put Data File in Python So It Will Read

Watch Now This tutorial has a related video course created by the Real Python team. Scout information technology together with the written tutorial to deepen your understanding: Reading and Writing Files in Python

I of the most common tasks that you can do with Python is reading and writing files. Whether it's writing to a simple text file, reading a complicated server log, or even analyzing raw byte data, all of these situations require reading or writing a file.

In this tutorial, you'll acquire:

- What makes up a file and why that'south important in Python

- The basics of reading and writing files in Python

- Some basic scenarios of reading and writing files

This tutorial is mainly for beginner to intermediate Pythonistas, but there are some tips in hither that more than advanced programmers may appreciate besides.

What Is a File?

Before nosotros can become into how to work with files in Python, information technology's important to empathise what exactly a file is and how modern operating systems handle some of their aspects.

At its core, a file is a face-to-face fix of bytes used to shop data. This information is organized in a specific format and can exist annihilation as simple as a text file or as complicated as a programme executable. In the end, these byte files are and so translated into binary 1 and 0 for easier processing by the computer.

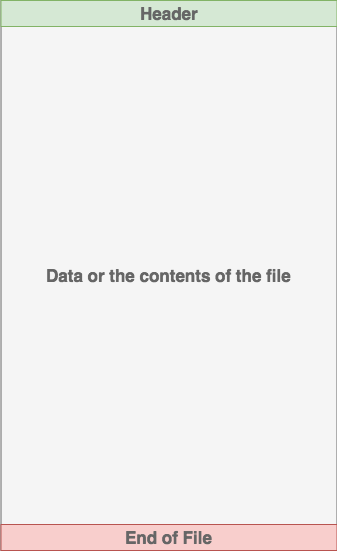

Files on most modern file systems are equanimous of 3 chief parts:

- Header: metadata near the contents of the file (file name, size, type, and so on)

- Information: contents of the file every bit written by the creator or editor

- Stop of file (EOF): special graphic symbol that indicates the finish of the file

What this data represents depends on the format specification used, which is typically represented by an extension. For example, a file that has an extension of .gif nearly likely conforms to the Graphics Interchange Format specification. There are hundreds, if not thousands, of file extensions out there. For this tutorial, y'all'll merely deal with .txt or .csv file extensions.

File Paths

When you access a file on an operating system, a file path is required. The file path is a string that represents the location of a file. It's cleaved upwardly into 3 major parts:

- Folder Path: the file folder location on the file system where subsequent folders are separated past a forward slash

/(Unix) or backslash\(Windows) - File Proper noun: the actual name of the file

- Extension: the end of the file path pre-pended with a period (

.) used to indicate the file type

Here'south a quick example. Let's say y'all accept a file located within a file structure like this:

/ │ ├── path/ | │ │ ├── to/ │ │ └── cats.gif │ │ │ └── dog_breeds.txt | └── animals.csv Let's say you wanted to access the cats.gif file, and your electric current location was in the same binder as path. In order to access the file, you demand to become through the path folder then the to folder, finally arriving at the cats.gif file. The Folder Path is path/to/. The File Name is cats. The File Extension is .gif. So the total path is path/to/cats.gif.

Now permit's say that your current location or electric current working directory (cwd) is in the to folder of our instance folder structure. Instead of referring to the cats.gif by the full path of path/to/cats.gif, the file can be but referenced by the file proper name and extension cats.gif.

/ │ ├── path/ | │ | ├── to/ ← Your electric current working directory (cwd) is here | │ └── cats.gif ← Accessing this file | │ | └── dog_breeds.txt | └── animals.csv But what about dog_breeds.txt? How would you access that without using the full path? You can utilize the special characters double-dot (..) to move 1 directory up. This means that ../dog_breeds.txt will reference the dog_breeds.txt file from the directory of to:

/ │ ├── path/ ← Referencing this parent folder | │ | ├── to/ ← Current working directory (cwd) | │ └── cats.gif | │ | └── dog_breeds.txt ← Accessing this file | └── animals.csv The double-dot (..) can be chained together to traverse multiple directories above the current directory. For example, to access animals.csv from the to folder, you would use ../../animals.csv.

Line Endings

1 problem often encountered when working with file data is the representation of a new line or line ending. The line ending has its roots from back in the Morse Code era, when a specific pro-sign was used to communicate the end of a transmission or the stop of a line.

Afterwards, this was standardized for teleprinters by both the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and the American Standards Association (ASA). ASA standard states that line endings should use the sequence of the Wagon Return (CR or \r) and the Line Feed (LF or \n) characters (CR+LF or \r\due north). The ISO standard still allowed for either the CR+LF characters or merely the LF character.

Windows uses the CR+LF characters to betoken a new line, while Unix and the newer Mac versions utilise merely the LF character. This can cause some complications when you're processing files on an operating organization that is dissimilar than the file's source. Here's a quick case. Allow's say that we examine the file dog_breeds.txt that was created on a Windows system:

Pug\r\n Jack Russell Terrier\r\n English language Springer Spaniel\r\n German Shepherd\r\north Staffordshire Bull Terrier\r\n Cavalier King Charles Spaniel\r\n Gilt Retriever\r\n West Highland White Terrier\r\due north Boxer\r\n Border Terrier\r\n This aforementioned output will be interpreted on a Unix device differently:

Pug\r \n Jack Russell Terrier\r \n English Springer Spaniel\r \n High german Shepherd\r \northward Staffordshire Balderdash Terrier\r \northward Cavalier King Charles Spaniel\r \north Gold Retriever\r \n West Highland White Terrier\r \n Boxer\r \due north Border Terrier\r \n This can make iterating over each line problematic, and you may demand to account for situations like this.

Character Encodings

Another mutual trouble that you may face is the encoding of the byte data. An encoding is a translation from byte data to human readable characters. This is typically washed by assigning a numerical value to represent a graphic symbol. The two virtually common encodings are the ASCII and UNICODE Formats. ASCII tin can but store 128 characters, while Unicode can comprise up to 1,114,112 characters.

ASCII is actually a subset of Unicode (UTF-8), meaning that ASCII and Unicode share the aforementioned numerical to character values. It's important to annotation that parsing a file with the incorrect graphic symbol encoding can lead to failures or misrepresentation of the character. For instance, if a file was created using the UTF-eight encoding, and you try to parse it using the ASCII encoding, if at that place is a character that is outside of those 128 values, and so an error will be thrown.

Opening and Endmost a File in Python

When you lot want to work with a file, the showtime thing to do is to open up it. This is washed by invoking the open() congenital-in function. open() has a unmarried required argument that is the path to the file. open up() has a single return, the file object:

file = open ( 'dog_breeds.txt' ) After you open a file, the next thing to larn is how to close it.

Information technology's of import to call back that it's your responsibleness to close the file. In nearly cases, upon termination of an awarding or script, a file will exist closed eventually. However, in that location is no guarantee when exactly that volition happen. This can lead to unwanted behavior including resource leaks. It's as well a best practice inside Python (Pythonic) to make certain that your code behaves in a fashion that is well defined and reduces any unwanted behavior.

When you're manipulating a file, there are ii ways that you can use to ensure that a file is closed properly, even when encountering an mistake. The outset style to close a file is to employ the try-finally block:

reader = open up ( 'dog_breeds.txt' ) try : # Further file processing goes here finally : reader . shut () If you're unfamiliar with what the try-finally cake is, bank check out Python Exceptions: An Introduction.

The second style to shut a file is to utilize the with statement:

with open ( 'dog_breeds.txt' ) as reader : # Further file processing goes here The with statement automatically takes intendance of closing the file once it leaves the with block, even in cases of mistake. I highly recommend that you use the with statement as much every bit possible, as it allows for cleaner code and makes handling any unexpected errors easier for you.

Well-nigh likely, yous'll also want to use the second positional statement, mode. This argument is a string that contains multiple characters to correspond how you desire to open the file. The default and most common is 'r', which represents opening the file in read-only mode as a text file:

with open ( 'dog_breeds.txt' , 'r' ) every bit reader : # Further file processing goes here Other options for modes are fully documented online, simply the almost commonly used ones are the following:

| Character | Meaning |

|---|---|

'r' | Open for reading (default) |

'w' | Open for writing, truncating (overwriting) the file first |

'rb' or 'wb' | Open in binary way (read/write using byte data) |

Let's go back and talk a little about file objects. A file object is:

"an object exposing a file-oriented API (with methods such equally

read()orwrite()) to an underlying resource." (Source)

In that location are three different categories of file objects:

- Text files

- Buffered binary files

- Raw binary files

Each of these file types are divers in the io module. Hither's a quick rundown of how everything lines up.

Text File Types

A text file is the near common file that you'll encounter. Hither are some examples of how these files are opened:

open ( 'abc.txt' ) open up ( 'abc.txt' , 'r' ) open ( 'abc.txt' , 'west' ) With these types of files, open() will return a TextIOWrapper file object:

>>>

>>> file = open up ( 'dog_breeds.txt' ) >>> type ( file ) <class '_io.TextIOWrapper'> This is the default file object returned by open up().

Buffered Binary File Types

A buffered binary file type is used for reading and writing binary files. Here are some examples of how these files are opened:

open ( 'abc.txt' , 'rb' ) open ( 'abc.txt' , 'wb' ) With these types of files, open() will return either a BufferedReader or BufferedWriter file object:

>>>

>>> file = open ( 'dog_breeds.txt' , 'rb' ) >>> type ( file ) <grade '_io.BufferedReader'> >>> file = open ( 'dog_breeds.txt' , 'wb' ) >>> type ( file ) <class '_io.BufferedWriter'> Raw File Types

A raw file type is:

"generally used equally a low-level building-cake for binary and text streams." (Source)

It is therefore not typically used.

Hither'due south an example of how these files are opened:

open up ( 'abc.txt' , 'rb' , buffering = 0 ) With these types of files, open() volition return a FileIO file object:

>>>

>>> file = open ( 'dog_breeds.txt' , 'rb' , buffering = 0 ) >>> type ( file ) <class '_io.FileIO'> Reading and Writing Opened Files

Once you've opened up a file, y'all'll want to read or write to the file. First off, allow's cover reading a file. There are multiple methods that tin be called on a file object to help yous out:

| Method | What It Does |

|---|---|

.read(size=-i) | This reads from the file based on the number of size bytes. If no statement is passed or None or -1 is passed, then the entire file is read. |

.readline(size=-1) | This reads at most size number of characters from the line. This continues to the finish of the line and so wraps back effectually. If no statement is passed or None or -ane is passed, and then the entire line (or residue of the line) is read. |

.readlines() | This reads the remaining lines from the file object and returns them equally a list. |

Using the aforementioned dog_breeds.txt file you used above, let's become through some examples of how to use these methods. Hither'due south an example of how to open and read the entire file using .read():

>>>

>>> with open up ( 'dog_breeds.txt' , 'r' ) equally reader : >>> # Read & impress the unabridged file >>> print ( reader . read ()) Pug Jack Russell Terrier English Springer Spaniel German Shepherd Staffordshire Balderdash Terrier Condescending King Charles Spaniel Gold Retriever Westward Highland White Terrier Boxer Edge Terrier Hither'southward an example of how to read v bytes of a line each fourth dimension using the Python .readline() method:

>>>

>>> with open ( 'dog_breeds.txt' , 'r' ) as reader : >>> # Read & impress the first 5 characters of the line 5 times >>> print ( reader . readline ( 5 )) >>> # Notice that line is greater than the 5 chars and continues >>> # downwardly the line, reading 5 chars each time until the end of the >>> # line and then "wraps" around >>> print ( reader . readline ( v )) >>> print ( reader . readline ( 5 )) >>> impress ( reader . readline ( 5 )) >>> print ( reader . readline ( five )) Pug Jack Russe ll Te rrier Here's an example of how to read the entire file every bit a listing using the Python .readlines() method:

>>>

>>> f = open ( 'dog_breeds.txt' ) >>> f . readlines () # Returns a list object ['Pug\n', 'Jack Russell Terrier\northward', 'English Springer Spaniel\n', 'German Shepherd\n', 'Staffordshire Bull Terrier\northward', 'Cavalier Male monarch Charles Spaniel\n', 'Golden Retriever\n', 'West Highland White Terrier\n', 'Boxer\north', 'Border Terrier\n'] The to a higher place example can likewise be washed past using list() to create a list out of the file object:

>>>

>>> f = open ( 'dog_breeds.txt' ) >>> list ( f ) ['Pug\north', 'Jack Russell Terrier\north', 'English language Springer Spaniel\northward', 'German Shepherd\n', 'Staffordshire Bull Terrier\northward', 'Cavalier King Charles Spaniel\due north', 'Gold Retriever\n', 'W Highland White Terrier\n', 'Boxer\n', 'Border Terrier\n'] Iterating Over Each Line in the File

A common thing to practise while reading a file is to iterate over each line. Hither's an example of how to use the Python .readline() method to perform that iteration:

>>>

>>> with open ( 'dog_breeds.txt' , 'r' ) as reader : >>> # Read and print the entire file line by line >>> line = reader . readline () >>> while line != '' : # The EOF char is an empty string >>> print ( line , finish = '' ) >>> line = reader . readline () Pug Jack Russell Terrier English Springer Spaniel German Shepherd Staffordshire Bull Terrier Cavalier King Charles Spaniel Aureate Retriever West Highland White Terrier Boxer Border Terrier Another manner you could iterate over each line in the file is to employ the Python .readlines() method of the file object. Remember, .readlines() returns a listing where each element in the list represents a line in the file:

>>>

>>> with open ( 'dog_breeds.txt' , 'r' ) as reader : >>> for line in reader . readlines (): >>> impress ( line , terminate = '' ) Pug Jack Russell Terrier English Springer Spaniel German Shepherd Staffordshire Bull Terrier Cavalier King Charles Spaniel Golden Retriever West Highland White Terrier Boxer Border Terrier However, the to a higher place examples tin can be further simplified by iterating over the file object itself:

>>>

>>> with open ( 'dog_breeds.txt' , 'r' ) as reader : >>> # Read and print the entire file line by line >>> for line in reader : >>> print ( line , end = '' ) Pug Jack Russell Terrier English Springer Spaniel German language Shepherd Staffordshire Balderdash Terrier Condescending King Charles Spaniel Golden Retriever Westward Highland White Terrier Boxer Edge Terrier This last approach is more Pythonic and can be quicker and more retentivity efficient. Therefore, it is suggested you use this instead.

At present let's dive into writing files. As with reading files, file objects have multiple methods that are useful for writing to a file:

| Method | What It Does |

|---|---|

.write(string) | This writes the string to the file. |

.writelines(seq) | This writes the sequence to the file. No line endings are appended to each sequence detail. Information technology'south upward to you to add the appropriate line ending(s). |

Hither's a quick example of using .write() and .writelines():

with open ( 'dog_breeds.txt' , 'r' ) as reader : # Note: readlines doesn't trim the line endings dog_breeds = reader . readlines () with open ( 'dog_breeds_reversed.txt' , 'w' ) as writer : # Alternatively you lot could use # author.writelines(reversed(dog_breeds)) # Write the dog breeds to the file in reversed lodge for breed in reversed ( dog_breeds ): author . write ( breed ) Working With Bytes

Sometimes, yous may demand to piece of work with files using byte strings. This is washed past adding the 'b' character to the fashion argument. All of the same methods for the file object apply. However, each of the methods expect and return a bytes object instead:

>>>

>>> with open ( 'dog_breeds.txt' , 'rb' ) as reader : >>> print ( reader . readline ()) b'Pug\n' Opening a text file using the b flag isn't that interesting. Let's say we have this cute picture of a Jack Russell Terrier (jack_russell.png):

You tin actually open up that file in Python and examine the contents! Since the .png file format is well divers, the header of the file is viii bytes broken up similar this:

| Value | Estimation |

|---|---|

0x89 | A "magic" number to signal that this is the outset of a PNG |

0x50 0x4E 0x47 | PNG in ASCII |

0x0D 0x0A | A DOS mode line catastrophe \r\n |

0x1A | A DOS fashion EOF character |

0x0A | A Unix style line ending \n |

Sure plenty, when you lot open the file and read these bytes individually, you can see that this is indeed a .png header file:

>>>

>>> with open ( 'jack_russell.png' , 'rb' ) as byte_reader : >>> impress ( byte_reader . read ( 1 )) >>> print ( byte_reader . read ( 3 )) >>> print ( byte_reader . read ( 2 )) >>> print ( byte_reader . read ( 1 )) >>> impress ( byte_reader . read ( 1 )) b'\x89' b'PNG' b'\r\n' b'\x1a' b'\n' A Total Example: dos2unix.py

Let'due south bring this whole thing home and look at a total example of how to read and write to a file. The following is a dos2unix like tool that will convert a file that contains line endings of \r\north to \north.

This tool is cleaved up into 3 major sections. The first is str2unix(), which converts a string from \r\north line endings to \n. The second is dos2unix(), which converts a string that contains \r\north characters into \n. dos2unix() calls str2unix() internally. Finally, at that place's the __main__ block, which is called simply when the file is executed as a script. Think of it as the primary office found in other programming languages.

""" A simple script and library to convert files or strings from dos similar line endings with Unix similar line endings. """ import argparse import bone def str2unix ( input_str : str ) -> str : r """ Converts the string from \r\n line endings to \n Parameters ---------- input_str The string whose line endings volition exist converted Returns ------- The converted string """ r_str = input_str . replace ( ' \r\northward ' , ' \n ' ) render r_str def dos2unix ( source_file : str , dest_file : str ): """ Converts a file that contains Dos like line endings into Unix like Parameters ---------- source_file The path to the source file to be converted dest_file The path to the converted file for output """ # Annotation: Could add file beingness checking and file overwriting # protection with open up ( source_file , 'r' ) as reader : dos_content = reader . read () unix_content = str2unix ( dos_content ) with open ( dest_file , 'westward' ) as author : writer . write ( unix_content ) if __name__ == "__main__" : # Create our Argument parser and set its description parser = argparse . ArgumentParser ( description = "Script that converts a DOS like file to an Unix like file" , ) # Add the arguments: # - source_file: the source file we want to catechumen # - dest_file: the destination where the output should go # Note: the use of the argument blazon of argparse.FileType could # streamline some things parser . add_argument ( 'source_file' , aid = 'The location of the source ' ) parser . add_argument ( '--dest_file' , help = 'Location of dest file (default: source_file appended with `_unix`' , default = None ) # Parse the args (argparse automatically grabs the values from # sys.argv) args = parser . parse_args () s_file = args . source_file d_file = args . dest_file # If the destination file wasn't passed, then assume nosotros want to # create a new file based on the old i if d_file is None : file_path , file_extension = os . path . splitext ( s_file ) d_file = f ' { file_path } _unix { file_extension } ' dos2unix ( s_file , d_file ) Tips and Tricks

Now that you've mastered the basics of reading and writing files, here are some tips and tricks to help you lot abound your skills.

__file__

The __file__ aspect is a special attribute of modules, similar to __name__. It is:

"the pathname of the file from which the module was loaded, if it was loaded from a file." (Source

Here's a existent world instance. In one of my by jobs, I did multiple tests for a hardware device. Each test was written using a Python script with the examination script file name used as a championship. These scripts would then be executed and could print their status using the __file__ special attribute. Here's an example folder structure:

project/ | ├── tests/ | ├── test_commanding.py | ├── test_power.py | ├── test_wireHousing.py | └── test_leds.py | └── main.py Running chief.py produces the following:

>>> python chief.py tests/test_commanding.py Started: tests/test_commanding.py Passed! tests/test_power.py Started: tests/test_power.py Passed! tests/test_wireHousing.py Started: tests/test_wireHousing.py Failed! tests/test_leds.py Started: tests/test_leds.py Passed! I was able to run and get the status of all my tests dynamically through employ of the __file__ special attribute.

Appending to a File

Sometimes, yous may want to suspend to a file or start writing at the end of an already populated file. This is easily done past using the 'a' graphic symbol for the fashion argument:

with open up ( 'dog_breeds.txt' , 'a' ) as a_writer : a_writer . write ( ' \n Beagle' ) When you examine dog_breeds.txt once again, you'll come across that the beginning of the file is unchanged and Beagle is at present added to the end of the file:

>>>

>>> with open ( 'dog_breeds.txt' , 'r' ) as reader : >>> print ( reader . read ()) Pug Jack Russell Terrier English Springer Spaniel High german Shepherd Staffordshire Bull Terrier Condescending King Charles Spaniel Aureate Retriever West Highland White Terrier Boxer Border Terrier Beagle Working With Two Files at the Aforementioned Time

In that location are times when you may want to read a file and write to another file at the same time. If you use the instance that was shown when you were learning how to write to a file, it can actually be combined into the following:

d_path = 'dog_breeds.txt' d_r_path = 'dog_breeds_reversed.txt' with open ( d_path , 'r' ) equally reader , open up ( d_r_path , 'w' ) every bit writer : dog_breeds = reader . readlines () writer . writelines ( reversed ( dog_breeds )) Creating Your Own Context Managing director

At that place may come up a time when you'll need finer control of the file object by placing it within a custom class. When you do this, using the with statement tin can no longer exist used unless you add a few magic methods: __enter__ and __exit__. By adding these, you lot'll have created what'due south called a context manager.

__enter__() is invoked when calling the with statement. __exit__() is called upon exiting from the with statement block.

Here'south a template that you can use to brand your custom class:

form my_file_reader (): def __init__ ( cocky , file_path ): self . __path = file_path self . __file_object = None def __enter__ ( self ): self . __file_object = open ( cocky . __path ) return self def __exit__ ( self , type , val , tb ): self . __file_object . close () # Additional methods implemented below Now that you've got your custom class that is now a context manager, you can use it similarly to the open up() congenital-in:

with my_file_reader ( 'dog_breeds.txt' ) equally reader : # Perform custom class operations pass Here's a practiced case. Retrieve the cute Jack Russell epitome we had? Perhaps y'all want to open up other .png files but don't want to parse the header file each fourth dimension. Here's an example of how to do this. This example also uses custom iterators. If you're not familiar with them, bank check out Python Iterators:

form PngReader (): # Every .png file contains this in the header. Utilise it to verify # the file is indeed a .png. _expected_magic = b ' \x89 PNG \r\n\x1a\due north ' def __init__ ( self , file_path ): # Ensure the file has the right extension if not file_path . endswith ( '.png' ): raise NameError ( "File must be a '.png' extension" ) self . __path = file_path self . __file_object = None def __enter__ ( cocky ): cocky . __file_object = open ( cocky . __path , 'rb' ) magic = self . __file_object . read ( eight ) if magic != self . _expected_magic : raise TypeError ( "The File is not a properly formatted .png file!" ) render cocky def __exit__ ( self , type , val , tb ): self . __file_object . close () def __iter__ ( cocky ): # This and __next__() are used to create a custom iterator # Come across https://dbader.org/weblog/python-iterators return self def __next__ ( cocky ): # Read the file in "Chunks" # Encounter https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portable_Network_Graphics#%22Chunks%22_within_the_file initial_data = self . __file_object . read ( 4 ) # The file hasn't been opened or reached EOF. This ways we # can't go any further and then stop the iteration past raising the # StopIteration. if self . __file_object is None or initial_data == b '' : raise StopIteration else : # Each chunk has a len, type, data (based on len) and crc # Grab these values and return them every bit a tuple chunk_len = int . from_bytes ( initial_data , byteorder = 'large' ) chunk_type = self . __file_object . read ( 4 ) chunk_data = self . __file_object . read ( chunk_len ) chunk_crc = self . __file_object . read ( iv ) return chunk_len , chunk_type , chunk_data , chunk_crc You tin at present open up .png files and properly parse them using your custom context manager:

>>>

>>> with PngReader ( 'jack_russell.png' ) equally reader : >>> for fifty , t , d , c in reader : >>> print ( f " { 50 : 05 } , { t } , { c } " ) 00013, b'IHDR', b'v\x121k' 00001, b'sRGB', b'\xae\xce\x1c\xe9' 00009, b'pHYs', b'(<]\x19' 00345, b'iTXt', b"50\xc2'Y" 16384, b'IDAT', b'i\x99\x0c(' 16384, b'IDAT', b'\xb3\xfa\x9a$' 16384, b'IDAT', b'\xff\xbf\xd1\n' 16384, b'IDAT', b'\xc3\x9c\xb1}' 16384, b'IDAT', b'\xe3\x02\xba\x91' 16384, b'IDAT', b'\xa0\xa99=' 16384, b'IDAT', b'\xf4\x8b.\x92' 16384, b'IDAT', b'\x17i\xfc\xde' 16384, b'IDAT', b'\x8fb\x0e\xe4' 16384, b'IDAT', b')3={' 01040, b'IDAT', b'\xd6\xb8\xc1\x9f' 00000, b'IEND', b'\xaeB`\x82' Don't Re-Invent the Snake

There are common situations that you may come across while working with files. Well-nigh of these cases can be handled using other modules. Two common file types you may need to piece of work with are .csv and .json. Real Python has already put together some great articles on how to handle these:

- Reading and Writing CSV Files in Python

- Working With JSON Data in Python

Additionally, there are built-in libraries out in that location that y'all tin can utilise to aid you lot:

-

wave: read and write WAV files (audio) -

aifc: read and write AIFF and AIFC files (sound) -

sunau: read and write Dominicus AU files -

tarfile: read and write tar annal files -

zipfile: work with Goose egg athenaeum -

configparser: easily create and parse configuration files -

xml.etree.ElementTree: create or read XML based files -

msilib: read and write Microsoft Installer files -

plistlib: generate and parse Mac OS Ten.plistfiles

There are plenty more out at that place. Additionally there are even more third party tools bachelor on PyPI. Some popular ones are the following:

-

PyPDF2: PDF toolkit -

xlwings: read and write Excel files -

Pillow: paradigm reading and manipulation

Yous're a File Sorcerer Harry!

You did it! You now know how to work with files with Python, including some advanced techniques. Working with files in Python should now exist easier than always and is a rewarding feeling when you offset doing information technology.

In this tutorial you've learned:

- What a file is

- How to open and shut files properly

- How to read and write files

- Some advanced techniques when working with files

- Some libraries to work with common file types

If you have whatever questions, hit united states up in the comments.

Sentinel At present This tutorial has a related video course created by the Real Python squad. Watch it together with the written tutorial to deepen your understanding: Reading and Writing Files in Python

Source: https://realpython.com/read-write-files-python/

0 Response to "Where to Put Data File in Python So It Will Read"

Post a Comment